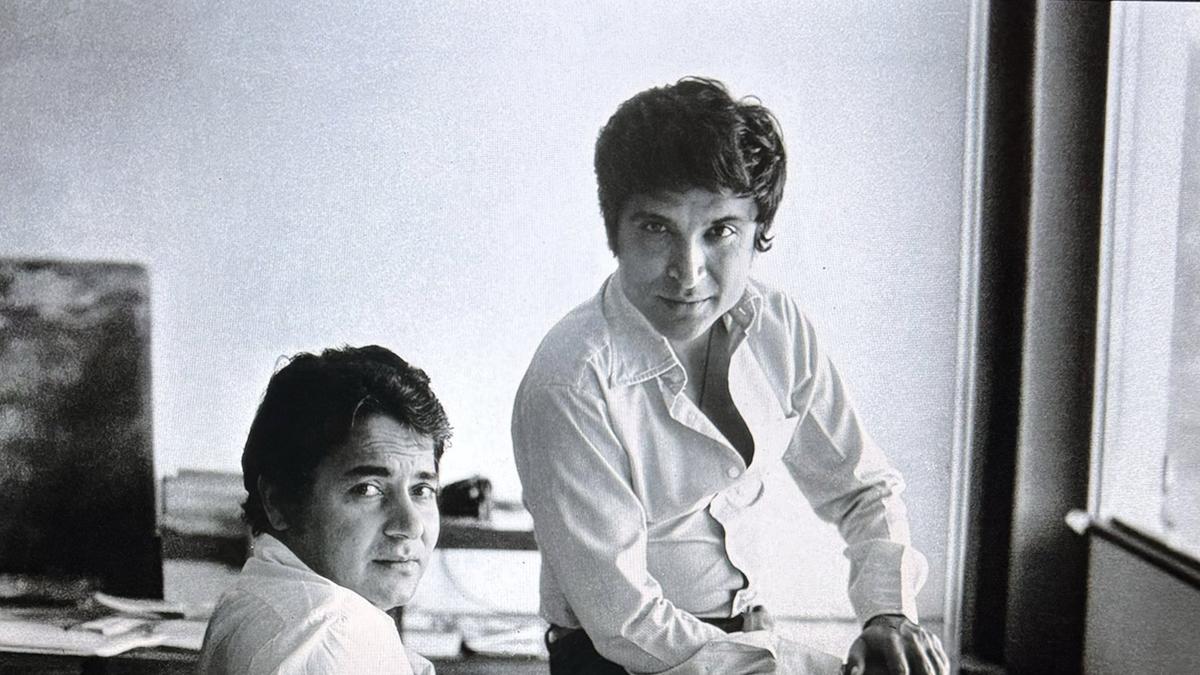

An enjoyable and timely study of the genius of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar that generates the warmth and coolth we associate with the screenwriter duoâs work, Angry Young Men, among many things, finds Vijay in his creatorsâ persona and thoughts.

The docu-series documents how Salim-Javed ushered the age of a writer in Hindi cinema in the 1970s with a middle-class hero who questions authority and seeks to rise the social ladder in no time. A product of their personal lives and political atmosphere, Vijay resonated with the youth anguished with the rising inflation, unemployment, and corruption.

Helmed by Namrata Rao, it discusses the dialogues that exploded like dynamite beneath the seats, the angst in their stories that left a deep impression on the armrests, and the sardonic humour that lit up the darkness of theatres. Speaking on behalf of the working class, the duo mainstreamed dissent when India was on the cusp of change with a series of characters that continue to live on in different forms in Bollywoodâs universe.

They had an astonishing strike rate at the box office, with 1975 as the defining year when Deewar and Sholay hit the turnstiles. The series doesnât speak in absolutes and allows the audience to build an opinion about two charismatic men who sound brash yet vulnerable.

A less-remembered scene in Zanjeer that makes a quiet entry in the middle of the series showcases what the angry young man is all about. An ebullient Mala seeking to build a beautiful home with suspended inspector Vijay shows him a magazine with curtain designs that she intends to put on the windows. Imploding in front of a corrupt system, Vijay remarks, âYes, we will cover the windows and I would not try to see whatâs happening in the world beyond them. I will shut my eyes to the deaths under the wheels of smugglers and if their cries reach my ears, I will shut them and look into your eyes or hide my face in your dark, thick hairs.â

With this scene, that still gives goosebumps, Salim-Javed buried the singing and dancing romantic hero who was constantly on a picnic in the 1960s, and a new, brooding protagonist was born. The series underlines that Zanjeer released in 1973 predates the call for total revolution and the Emergency that followed in 1975. That Salim-Javed were breathing the same air that a common man was inhaling, that both had father issues and could laugh in adversity perhaps ensured that Vijay was fleshed out on screen ahead of the groundswell in society. Similarly, in Deewar, when Vijay says he doesnât pick up the money thrown at him, he echoes the rejection faced by Salim Javed during their long struggle in the Bombay film industry.

In terms of format, the series follows the new OTT formula that we saw in The Romantics, a gushy take on Yash Chopra followed by Modern Masters: SS Rajamouli but Angry Young Men is a lot more perceptive and engaging without making a show of it.

Produced by the children of Akhtar and Khan (Salman Khan Films, Excel Entertainment, and Tiger Baby Films), it also runs the risk of being reduced to a family drama where relatives, friends, and industry insiders come together to record encomiums for posterity. However, the makers ensure that access doesnât lock the doors of creativity. The bytes are crisp and the narrative doesnât plod as Akhtar and Khan keep the anecdotes rolling.Â

Time has not wilted their gifted art of narration. When they talk about the short time nature allowed them to be with their mothers, it not only generates an emotional swell but provides an insight into the role of the mother figure in at least three of their blockbusters. Akhtar touches upon a raw nerve when he relates his experience with deprivation and hunger that refuses to leave his psyche. Their yearning for acceptance, the series suggests, became a leitmotif of their personalities that reflected in their writing. The outliers desperately wanted to be stars. It started with putting their names on the posters with a stencil and went up to seeking a lakh rupees more than Amitabh Bachchan at the acme of their careers. The series documents that their attitude cost them goodwill.

That Namrata is an illustrious editor helps in creating a narrative where much like Salim-Javedâs screenplays, a seed is planted only to bloom a few minutes later. From playing on their iconic line kitne aadmi the to introduce them to Akhtar reading out Krishan Chanderâs prose on the purpose of life with a tremor in his voice, Namrata keeps the style and substance in sync through the series. She doesnât shy away from probing knotty questions like the portrayal of women in their blockbusters and the treatment meted out to the spouses in their respective lives. Honey Irani, the ex-wife of Akhtar finds a Gabbar in him and the shots of Khanâs first wife Salma silently moving in and out of frames create intriguing imagery. The shots of Salman Khan as a son without his stardom must pique the interest of a filmmaker.

The things Khan and Akhtar say over the three episodes are not exactly straight from the oven. From their conviction in Amitabh Bachchan to predicting the business of their films, most of the stuff they speak about is spread over the Internet. Namrata has threaded those insights and archival material into a wholesome experience by putting them in the context of time and space with credible voices that put their legacy and the role of screenwriting in Hindi cinema in perspective.

There are passages where it seems the veterans have plotted interesting answers to all that has happened to them in their mind and they repeat it every time the camera turns on. So one keeps looking for unrehearsed moments. The light touches like when Akhtarâs daughter Zoya corrects her partner Reema Kagtiâs pronunciation of Zanjeer, or the way she interjects when Akhtar philosophises the idea of age, or for that matter when Akhtar says that it feels like he is asking for a job when photographer Ashutosh Gowarikar requests him to sit close to the edge of the seat for a portrait with Khan create a more tangible texture.

While discussing his knack for writing unforgettable villains, Akhtar says how children love to first see the tiger in the zoo. The birds come much later in their itinerary. Similarly, the audiences want to know the reasons for the separation of âone body, one mind, one voiceâ, as Jaya Bachchan describes the duo. The series doesnât add much to what is already there in the public domain. It also doesnât consider when the duo lost some of their fire with Dostana, Govind Nihalani picked up the baton to create his version of the angry young man in Ardh Satya (1983).

Billa No 786, perhaps, their most powerful narrative device, is conspicuous by its absence. The series is also silent on how their understanding of religion informed their writing and relationship; Akhtar is an avowed atheist while Khan thinks twice before removing the droplets of sweat from his forehead lest his destiny is wiped off. If this is said in zest, he goes on to quote the Prophet on the value of a workerâs sweat. In recent years, the right-wing ecosystem held the duo responsible for introducing narrative devices that promoted one faith and questioned the other. One would have loved to know their take on the conversation of protagonists with God in their films. Senior Bachchan hints at how it worked with the audience for the first time but Namrata doesnât carry the conversation forward.

Similarly, in their blockbusters, they made trade union leaders heroes and capitalists villains. In Deewar, the main antagonist played by Madan Puri is named Samant, perhaps, to make him sound like a knight of samantwadi (feudal) ideology. Salim-Javed are silent on Hindi filmsâ transition to post-liberalised India where Hindutva is a mainstream political thought and secular values seem to have corroded.

During a conversation on Imaan Dharam, their only major flop, Akhtar says in a metaphorical tone that usually they added a pinch of salt to their bread but in Imaan Dharam, they made the whole bread out of namak. In the case of Angry Young Men, one can say the layers of bread are honeyed, but it is not a hagiography.

Angry Young Men is currently streaming on Amazon Prime