Electric SUVs XEV9e and BE6 on the production line at Mahindra & Mahindra’s Chakan plant near Pune

Image: Amit Verma

Jaideep Wadhwa, managing director of Sterling Gtake E-mobility, an auto components manufacturer, has a word of advice for India’s automakers. “Fold your hands and pray to God this crisis is over soon,” he says, “because there is no other option in the immediate future.”

Wadhwa’s reference is to the ongoing shortage of rare earth magnets, which seems to be hurting India’s 20 lakh vehicles-a-year automotive industry—counting all two-wheelers, three-wheelers and passenger vehicles sold in the world’s third-largest market. Although most automakers are tight-lipped about the crisis, reports of unavoidable delays and disruption abound, specifically in the production of electric vehicles (EVs), for which rare earth magnets are critical.

If the supply of rare earth magnets is not resolved by the end of June, India’s auto sector could be looking at production disruptions by early August, causing delays in sales leading up to the festive season, which begins in October and usually accounts for between 30 percent and 35 percent of annual sales. Unconfirmed estimates peg the potential delays in production at two to six months with a possible price rise at 5 to 8 percent.

“I must point out a dark cloud on the horizon in terms of continued supply of rare earth magnets from China, which are an essential component of high-performance EV motors… any delay or disruption will start to seriously impact production by July,” Rakesh Sharma, executive director, Bajaj Auto, said during the fourth quarter results conference call on May 29. Bajaj has emerged as the largest in the electric scooter market during the quarter between January and March 2025 with a 29 percent market share.

Already, this year is not going too well for India’s automakers, with the passenger vehicles segment growing only 3 percent during April-May this year over last year. Two-wheelers haven’t done any better, with a 7 percent decline, and with a decisive shift in the market towards electric, the rare earth shortage bodes ill. “Limited supplies mean that vehicles could become expensive or that discounts may disappear,” Ravi Bhatia, president and director at Jato Dynamics India, an automotive data and intelligence company, tells Forbes India.

The biggest players in the car market are not shouting Mayday yet, but the subtext of uncertainty is palpable, as is the search for alternative sources.

“As of now there is no disruption in our operation due to this issue. There is a lot of uncertainty, and the situation is continuously evolving.We are pursuing multiple solutions to ensure continuity in our operations,” said Maruti Suzuki, which is poised to launch its maiden EV.

RC Bhargava, Maruti Suzuki’s chairman, told Business Standard that the company had stocks of rare earth magnets till July-end. “We are also looking at alternatives, but there is nothing concrete to say at this moment,” he said.

In the short term, Tata Motors too said it was looking at a combination of inventory and alternative sources. “If it (crisis) continues forever, that’s a different issue to deal with. At this point, there is no panic button pressed because we believe the supplies are coming through,” PB Balaji, the group chief financial officer of Tata Motors Limited, said at a press conference on June 24.

“In the mid-to-long term, there are multiple solutions,” Shailesh Chandra, managing director of Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles Ltd and Tata Passenger Electric Mobility Ltd, adds. “In the mid-term, we’ll have to look for alternative countries and reduce the constitution or mix of the elements (rare earth) into the components. In the long term, we need to see how we can eliminate them completely.”

Similarly, Mahindra & Mahindra is looking to reduce the risk in its supply chain. “Currently Mahindra has inventory for affected parts to meet the production needs,” said a spokesperson. “We are de-risking our supply chain by sourcing assembled parts, exploring alternative materials, and working with SIAM (Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers, the industry association) and the Government of India to expedite certifications. We are closely collaborating with our suppliers to ensure there is no disruption to production.”

“Indian automakers currently have an inventory of about three to four weeks,” says Puneet Gupta, director at S&P Mobility, an automotive intelligence company. “But for production to continue in August, dispatches from China need to happen by the end of June. If that doesn’t happen, then there is a trickle-down effect with sales being disrupted during the festive season.”

Also read: Explainer: Why the world is fighting over rare earths

Why the fuss?

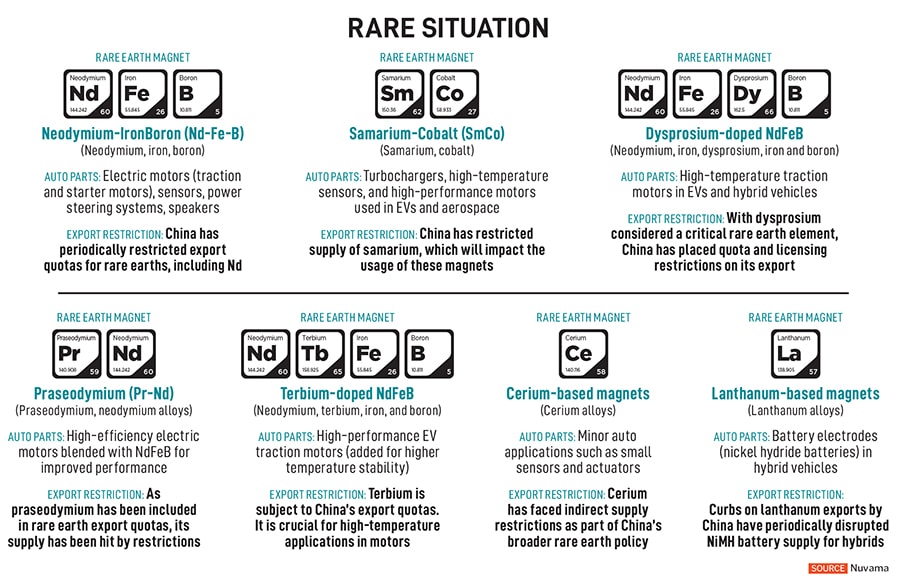

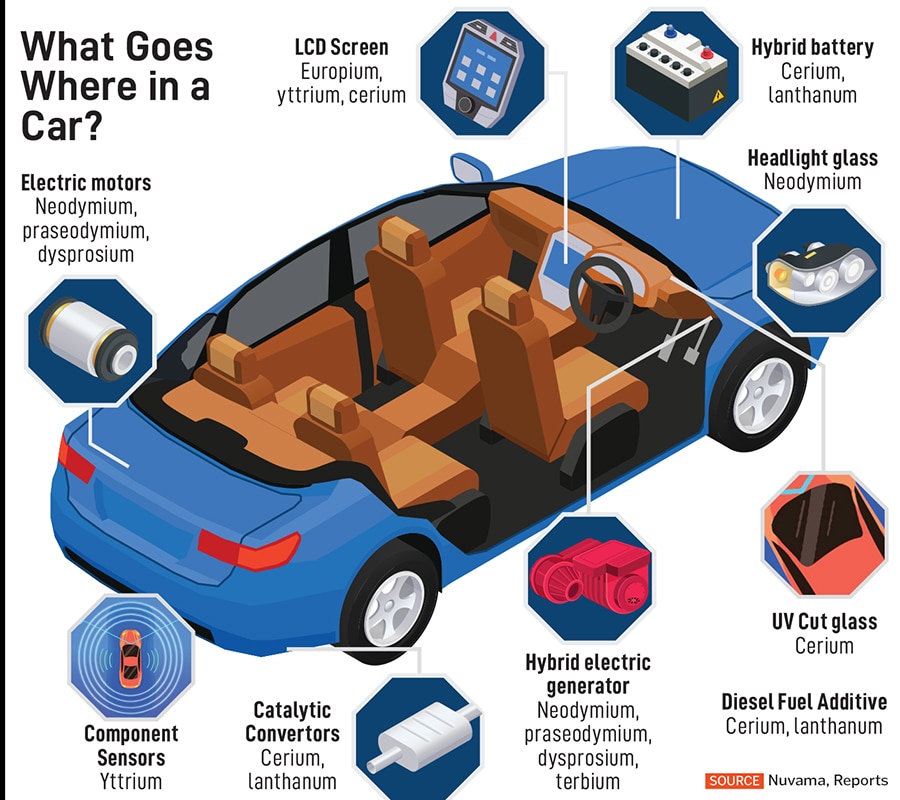

Magnets made from rare earth elements are far more powerful than conventionally made magnets and therefore are of critical importance in aerospace and EVs. The most popular rare earth magnets are neodymium-iron-boron and samarium-cobalt.

For the auto industry, which contributes 7 percent to India’s gross domestic product, rare earth magnets are crucial. “For traditional ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicles, magnets are used in components such as power steering motors and air conditioning systems,” says Harshvardhan Sharma, head of auto retail practice at Nomura Research Institute. “The role is essential, but the overall dependency is less than in EVs. However, in EVs, rare earth magnets play an indispensable role.”

Permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs), which are most used in EVs, depend on rare earth magnets for performance, compact design and efficiency. These motors are up to 20 percent more efficient than their induction motor counterparts, which do not use rare earth materials. With the global EV market expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 29 percent from 2022 to 2030, the role of rare earth magnets in this segment is critical, as they enable high-performance and energy efficiency.

A file photo of workers handling neodymium ingots at Neo Material Technologies Inc’s Magnequench factory in Tianjin, China

A file photo of workers handling neodymium ingots at Neo Material Technologies Inc’s Magnequench factory in Tianjin, China

Image: Doug Kanter / Bloomberg Via Getty Images

Though these elements are categorised as ‘rare’, they are relatively abundant, and often found in concentrations of metals such as copper and zinc. But, because they are mixed with other elements, making their mining a challenge, they are called rare earth elements. “The use of rare earth magnets is not just limited to the automotive sector,” adds Bhatia of Jato. “They find use in wind turbines, computers and so on. In 2023, the demand for rare earth magnets in India stood at 7,000 tonnes. That’s expected to go to 40,000 tonnes in the next 25 years.”

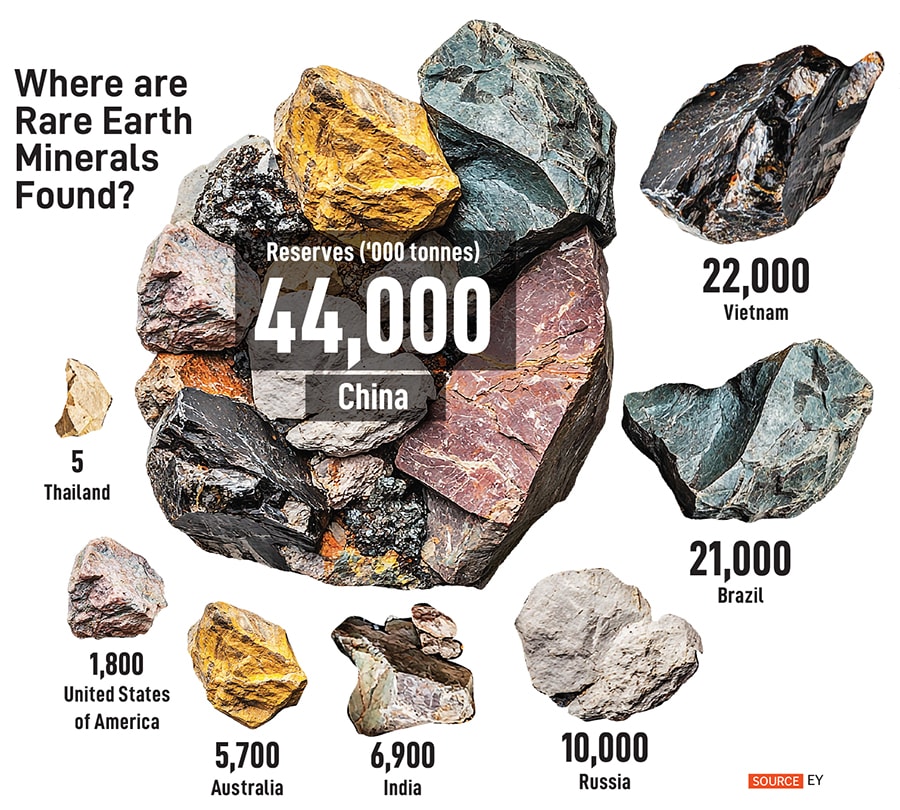

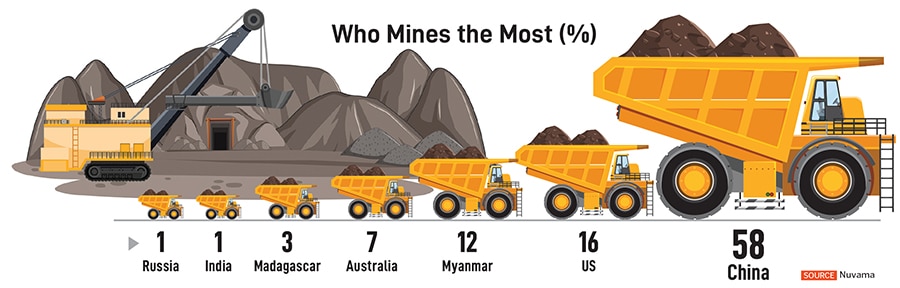

China has 40 percent of the world’s deposits of rare earth minerals. As much as 68 percent of all rare earth processing is done in China. And the country accounts for 92 percent of the global supply of rare earth magnets.

“In the 1990s, when Toyota Prius came out, it used permanent magnets for the first time,” says Wadhwa of Sterling Gtake. “What a permanent magnet does is that it enables the designer to reduce the size and weight of the motor quite significantly, as compared to an induction motor.”

The current crisis began to brew in April when, in retaliation to the fresh tariffs imposed by US President Donald Trump, China introduced export controls on rare earth materials, requiring end-use certification to ensure only non-military applications. Though the trade restrictions are not on assembled parts, imports of raw materials remain severely affected.

Under China’s new rules, importers must provide full disclosures and client declarations, including confirmation that the products would not be used in defence or re-exported to the US. The clearance process takes at least 45 days.

First, the Indian company needs to court notarise its papers regarding the end use. The Directorate General of Foreign Trade and the Ministry of External Affairs verify these documents and the end usage before submitting them to the Chinese embassy. The Chinese embassy then verifies them before approval.

The end-use certificates are then sent to the supplier of rare earth magnets in China. This supplier seeks approval from the Chinese government. Once the approval comes, the supplier sends the consignment to the Indian company.

In June, the Chinese government rejected Sona BLW Precision Forgings’ application to import rare earth magnets, making it the first Indian entity to face such a decision under China’s tightened export control regime. Today, 30 Indian firms are seeking permits from the Chinese government for rare earth magnet imports. The Indian government has stepped in and is attempting to sort out the issue diplomatically.

“We are making all the efforts to see that these essential items of imports can come to India,” India’s commerce secretary Sunil Barthwal said on June 16.

“I think this is an arm-twisting tactic,” Arun Malhotra, former managing director of Nissan Motors India and an auto sector expert, says. “If China wants to, they can have the parts shipped to India in seven days. But it’s also a wake-up call for us not to be reliant on one country. Today it’s magnets… tomorrow it could be something else.”

The government is working on a plan to incentivise production of rare earth minerals and magnets derived from them. The layout of this plan is likely to be in the range of ₹3,500 crore to ₹5,000 crore. “We must take this opportunity to understand the value chain,” adds Malhotra. “The production-linked incentive scheme has been slow, and we need to relook at how Make in India has been progressing. We are at a stage when EV sales are finding adoption, and we cannot afford to have anything that will halt that.”

China currently has the largest deposits of rare earth elements at 44 million tonnes. India has about 6.9 million tonnes. But it is in the mining and refining process that China invested heavily in the past, allowing it to refine as much as 90 percent of the global supply and giving it a stranglehold over the minerals.

India has a public sector company, Indian Rare Earths Limited, which has an established plant capacity of about 1 million tonnes a year of minerals processing capacity for ilmenite, rutile, zircon, sillimanite and garnet.

Sharma of Nomura says though India could tap into its reserves of rare earth materials—India has an estimated 6 percent of global rare earth reserves—tapping them and developing processing capacity would require significant investments, and this is likely to take several years.

“India did not build up rare earth refining capability. And the moment we spend our time doing that and developing it, China will change their supply strategy and we (India) are certain to be hit hard,” adds Bhatia.

India imported 870 tonnes of rare earth magnets, valued at ₹306 crore, in FY25. “In the short term, diversifying supply chains and investing in recycling technologies can mitigate the effects of the crisis,” says Sharma of Nomura.

Bhatia adds that at the moment, there are three options. “Companies must adjust their already-available inventory and work around it. The other is to look at alternative solutions such as Australia, Vietnam or Japan. The third is to set up joint ventures with companies in China.”

Gupta of S&P Mobility too says it makes no sense for India to follow what China has done. “China has spent decades finetuning the refining, and they started out on it before concerns over the environment were raised. Ideally, we must manage this diplomatically and by engaging with China smartly and by looking at other sources,” he says.

Extraction and processing of rare earth elements is a tedious process and generates radioactive waste, chemical waste, air pollution and water pollution.

The road ahead for automakers

EV penetration in India is still low, though the government has set ambitious targets for the next five years. Ominously, the rare earth magnet shortage brings back memories of 2021, when the country’s automobile industry was hobbled by a shortage of semiconductors, disrupting production schedules.

“The main impact will be felt in model launches,” financial services firm Nuvama said in a report. “The domestic launch of e-Vitara has been delayed and Maruti Suzuki has slashed its production target to 67,000 units from 85,000 units.” e-Vitara is the electric version of Maruti’s popular sports utility vehicle.

Nuvama says the impact will be limited to EVs. “Among two-wheeler makers, the greatest impact will be on pure play EV players like Ola and Ather,” it said.

Sharma of Nomura says: “By establishing a domestic supply chain for rare earths, India can reduce reliance on imports and mitigate the geopolitical risks tied to rare earth material shortages. Additionally, the government could incentivise the growth of the EV battery recycling market, which could help recover rare earth magnets from end-of-life EVs.”

The deepening crisis has prompted India to suspend a 13-year-old agreement on rare earth exports to Japan and seek partnerships with mineral-rich countries such as Australia, Argentina and Brazil. “Automakers must consider diversifying for strategic partnerships with countries like Australia, which has become one of the largest producers of rare earths, or invest in processing capabilities within India itself,” adds Sharma of Nomura.

There is also the option of induction motors, which, although not as efficient as permanent magnet motors, offer cost-effectiveness and have a long history of use in other industries. Induction motors power a quarter of the EVs sold globally, but not in high-performance EVs due to their lower efficiency compared to PMSMs. The performance gap, however, is shrinking and innovations such as hybrid motors are being explored.

In May, Faridabad-based Sterling Gtake E-Mobility tied up with UK-based Advanced Electric Machines (AEM) to manufacture rare earth-free magnets. AEM has patented its technology and the partnership with Sterling would help commercialise the sale of these magnets.

Another alternative is ferrite-based magnets, which are cheaper and more abundant than rare earth magnets, albeit less efficient. Research is on, but estimates suggest it will take years before they can match the performance of rare earth magnets.

“In the medium-to-long term, significant investments in alternative motor technologies will be necessary for automakers to reduce their dependence on rare earth magnets,” adds Sharma of Nomura.

Until then, they can pray.

Leave a Reply