Though divided by fierce scientific rivalry — Golgi defending the idea of a continuous nerve network, Cajal championing the “neuron doctrine”, their discoveries together reshaped biology. Golgi’s revolutionary staining method revealed the hidden architecture of nerve cells, while Cajal’s interpretations proved that the nervous system was made of individual units: neurons. Their Nobel Prize marked not only a clash of ideas but the birth of modern neuroscience, and its impact extends to global health, neurology, psychiatry and public policy even today.

Early years

Camillo Golgi was born on July 7, 1843, in Corteno, Italy. From modest beginnings, he studied medicine at the University of Pavia and began his career as a physician in psychiatric and hospital wards. With limited resources, he improvised laboratory space in his own kitchen. Out of these unassuming beginnings came one of the most transformative methods in biology: the silver chromate stain (a chemical reaction used to create a brick-red or brown-black color to make certain things, especially cells, visible under a microscope).

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, born on May 1, 1852, in Petilla de Aragón, Spain, was raised under the stern discipline of his physician father. A gifted illustrator who once dreamed of becoming an artist, he redirected his talents toward science. His eye for detail and artistic hand later gave rise to some of the most iconic images in the history of medicine: the first clear drawings of neurons.

Golgi’s black reaction

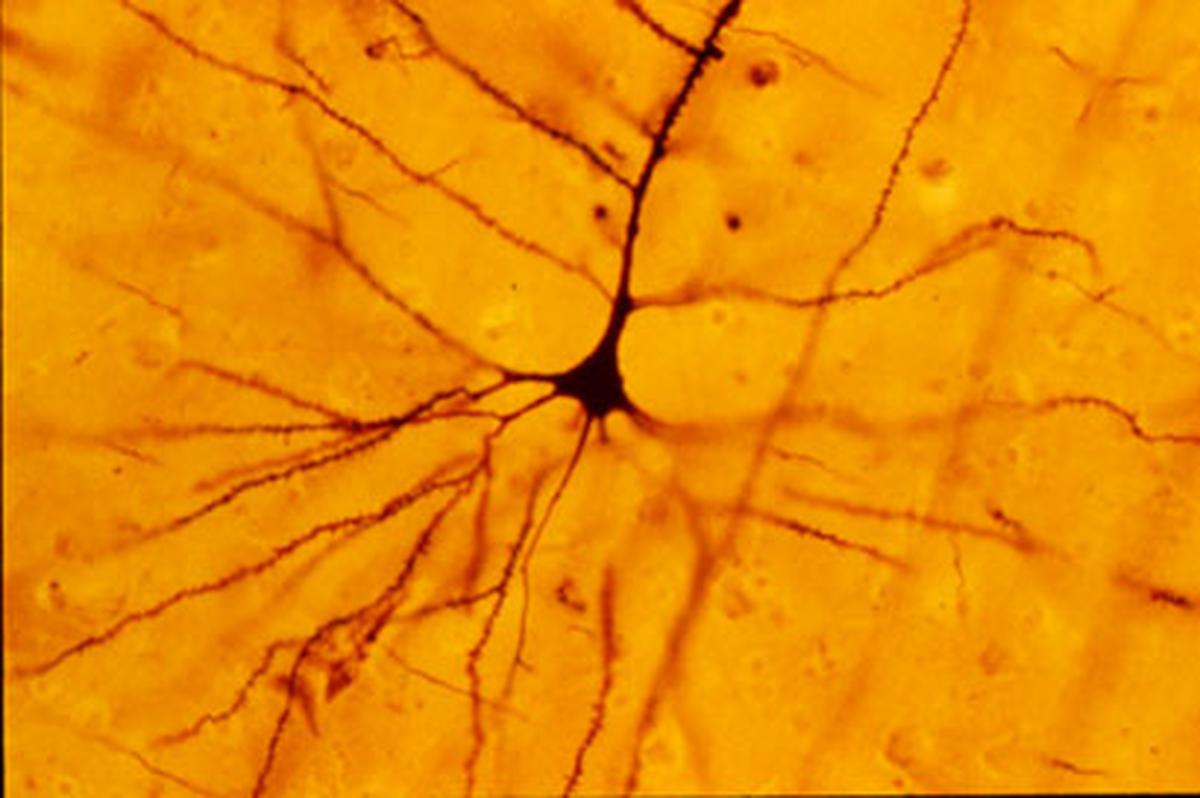

In 1873, Golgi developed the reazione nera — the “black reaction.” The method impregnated a small fraction of nerve cells with silver chromate, revealing their entire shape under the microscope: cell body, dendrites, and axon. For the first time, the nervous system was visible not as a blur but as a forest of branching, living structures.

A human neocortical pyramidal neuron stained via Golgi technique

| Photo Credit:

wikimedia commons/Bob Jacobs, Colorado College

Golgi interpreted these findings through the lens of the reticular theory, which held that neurons were fused into a single continuous web. Though this theory was later overturned, Golgi’s staining method became indispensable. His work extended beyond neuroanatomy: he also discovered the Golgi apparatus, a structure critical to cell biology, protein processing, and viral replication. This finding remains essential to global research in cancer, infectious disease and vaccine development.

Cajal’s neuron doctrine

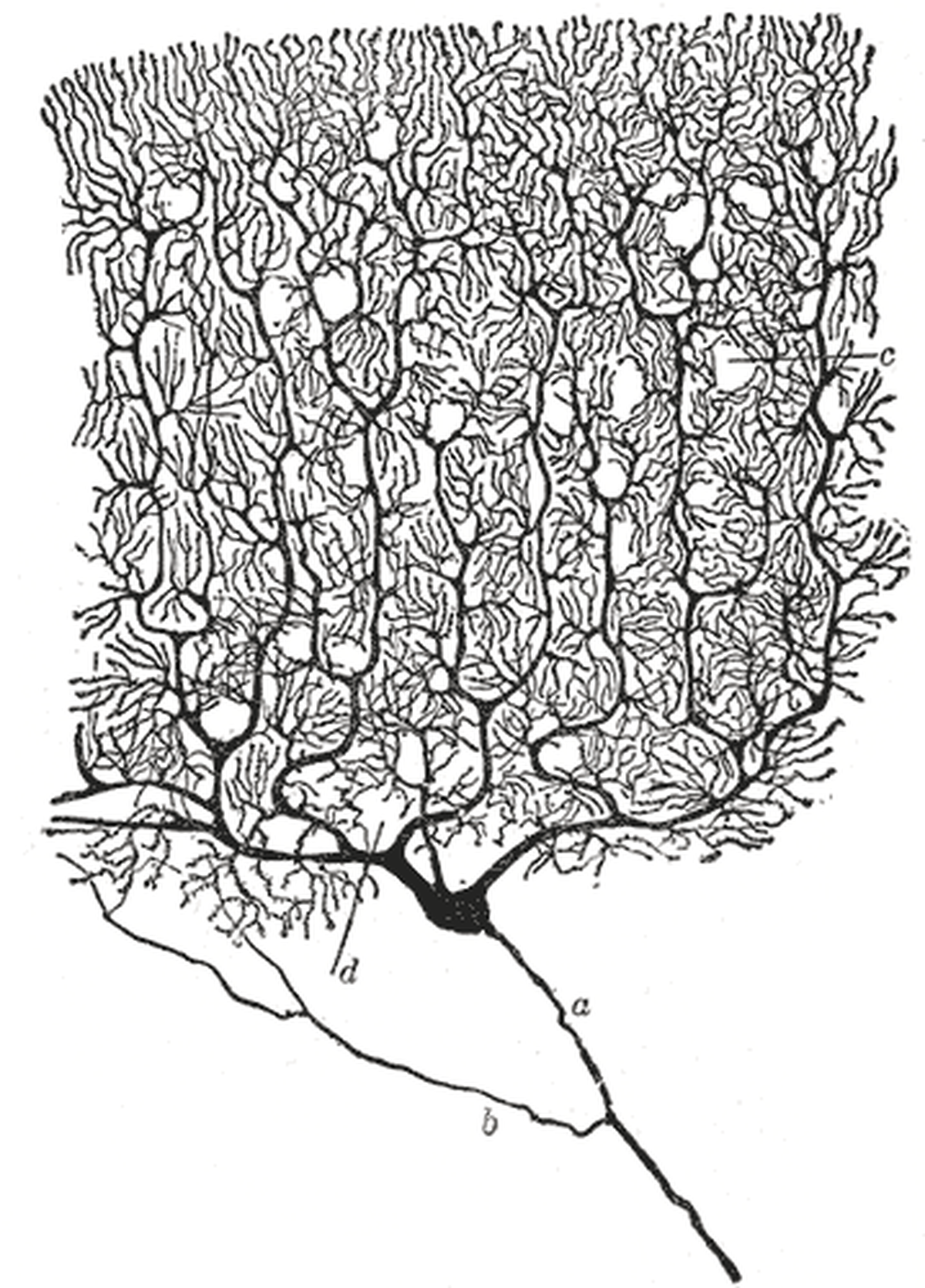

When Cajal encountered Golgi’s method in the 1880s, he applied it with extraordinary precision and vision. His meticulous observations showed that neurons were discrete cells that communicated at points of contact, not through continuity. He articulated the neuron doctrine, proving that the nervous system was cellular, just like other tissues of the body.

Drawing of a Purkinje cell in the cerebellum cortex done by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, demonstrating Golgi’s staining method to reveal fine detail

| Photo Credit:

wikimedia commons

Cajal’s illustrations of the retina, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex captured not only the elegance of neuronal networks but also the principles of brain function. He demonstrated the one-way flow of information in neurons, a concept later foundational for understanding synapses and signal transmission.

His neuron doctrine transformed medicine: it allowed diseases like epilepsy, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis to be understood as disorders of neuronal circuits rather than vague imbalances. His insights underpin psychiatry, neurology, and today’s mental health research.

Nobel prize and global influence

The Nobel Prize was awarded jointly, but it did not unify their scientific visions. In his Nobel lecture, Golgi defended the reticular theory. In his response, Cajal meticulously dismantled it, presenting overwhelming evidence for the neuron doctrine.

It was a rare instance where the Nobel stage showcased not consensus but conflict. Yet this rivalry proved fruitful: Golgi gave the world the method to see, and Cajal gave it the interpretation that would define a new science.

Today, WHO programmes addressing dementia, epilepsy, stroke, and neurological disorders rest on the neuron doctrine. By defining the brain as a cellular system, Cajal’s work provided the framework for modern neurological diagnostics and therapeutics that inform international guidelines. In 2014, UNESCO inscribed Ramón y Cajal’s scientific drawings in the “Memory of the World” register, highlighting their cultural and scientific value as foundational to modern neuroscience. The International Brain Research Organization (IBRO), founded in 1961, traces its intellectual lineage to Cajal’s call for global collaboration in neuroscience. It now partners with WHO to train scientists and clinicians in low- and middle-income countries. International projects such as the U.S. BRAIN Initiative and the European Union’s Human Brain Project explicitly acknowledge Cajal as their conceptual ancestor, building on his neuron doctrine to map and simulate the brain.

The discovery of the Golgi apparatus remains central in virology and immunology. During the COVID-19 pandemic, global vaccine research frequently referenced the Golgi’s role in protein trafficking — a reminder that Golgi’s insights extend far beyond the microscope slides of the 19th century.

Legacy in medicine and society

Golgi provided the methods and cellular discoveries that still underpin pathology, virology, and cell biology. His staining technique remains in use in modified forms like immunohistochemistry. His name lives on in the Golgi tendon organ, Golgi’s method, and the Golgi apparatus. Cajal offered the intellectual framework to understand the brain as a network of cells. His writings, from Histology of the Nervous System to philosophical essays, continue to inspire. He is remembered as the “father of modern neuroscience.”

Their rivalry illustrates that science often advances through tension between old paradigms and new insights. Today’s neuroscience , from molecular diagnostics to brain imaging and artificial intelligence traces its lineage back to Golgi and Cajal. Global strategies on mental health, dementia, and neurological disorders led by WHO, as well as international collaborations on brain mapping, all echo their discoveries. Golgi died in 1926; Cajal in 1934.

While Golgi gave science the ability to see the nervous system. Cajal gave science the language to describe and understand it. Together, they made the nervous system legible, laying the groundwork for a century of discoveries that continue to shape global health.

Published – October 19, 2025 03:30 pm IST

Leave a Reply