Helical paths are everywhere in the microscopic realm. Many bacteria and parasites don’t simply swim or glide in straight lines. In three dimensions, they trace corkscrew-like tracks through their surroundings. Malaria parasites, for example, glide through soft 3D gels and, in the skin of a bitten host, on paths that look like stretched springs.

For any such organism, the main challenge is noise. Random bursts of energy from their environment and fluctuations in their own force-generating machinery constantly try to twist it off course. Classic work on Escherichia coli bacteria has shown that a bacterium can lose its orientation within about a second because of rotational diffusion, i.e. collisions with surrounding molecules that slowly yet surely randomise its direction.

Yet malaria parasites and other similar microorganisms must stay roughly on track for tens of seconds or more if they’re to find nutrients and — in the parasite’s case — a blood vessel.

Do the twist

Earlier physical models typically described such microorganisms as self-propelled ‘beads’ buffeted by random noise. These models were mostly two-dimensional; sometimes they added a simple, constant torque to make the beads circle around. However they didn’t fully treat 3D helical motion in the presence of noise that had a memory, which is to say noise whose present value depends on its recent past. At the same time, geometry-based work on malaria parasites had shown how their curved, rod-like shape and flexibility helped them loop around obstacles and structures like blood vessels, but without describing how they could move that way in detail.

A new study by Heidelberg University researchers may have bridged this gap. They observed malaria parasites gliding through synthetic hydrogels and then reconstructed their paths using a model, publishing their findings in Nature Physics on November 24.

“Our new investigations show that malaria parasites move almost exclusively on right-handed helices in 3D environments,” Ulrich Schwarz, study coauthor and head of the Physics of Complex Biosystems group at the Institute for Theoretical Physics, Heidelberg University, said in a release.

From the data, the team found changes happening across two time scales: one at around 20 s and another at around 100 s. The 20 s matched the duration of one helical turn and in that time the parasite’s internal drive kept pushing in roughly the same way. The 100 s was how long the axis of the helix continued to point in one direction.

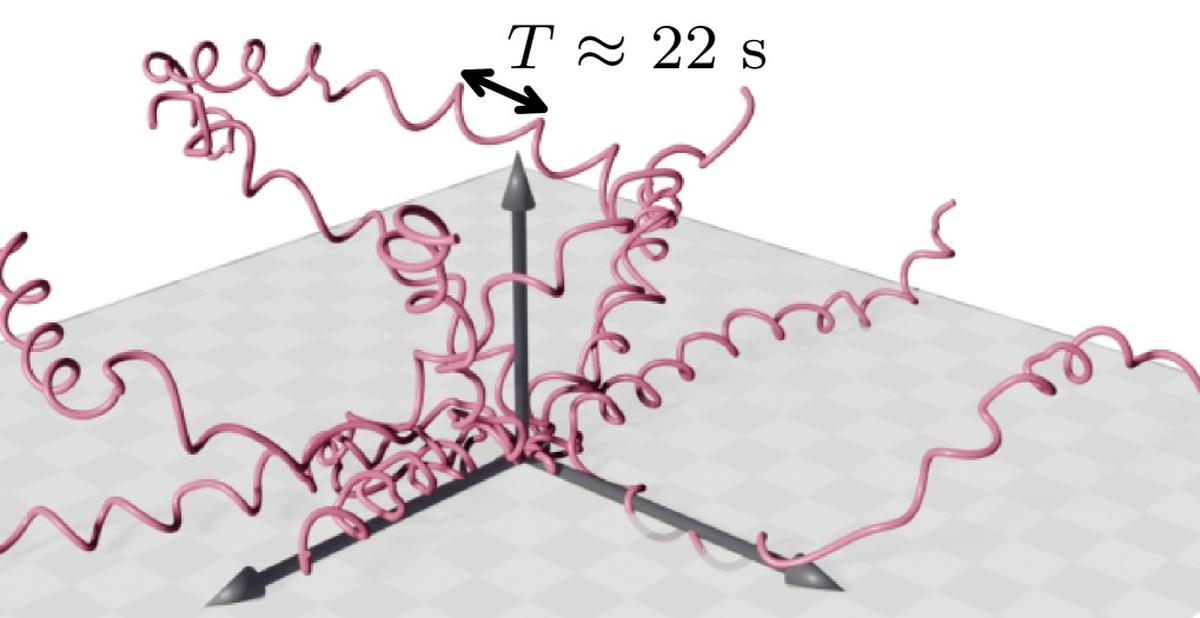

Reconstructed trajectories of malaria parasites gliding through synthetic hydrogels.

| Photo Credit:

arXiv:2501.18927v3

When loopy is better

Malaria sporozoites injected into human skin have to cover hundreds of micrometres to find a capillary that leads them to the liver. Older geometric models had already hinted that the natural distance across which a parasite makes a turn roughly matches the radius of small blood vessels, making it easier to loop around them. The new work has added a complementary question to this picture: given the noisy nature of the parasite’s internal mechanism, can following a helical path actually help it travel farther than a non-looping microorganism moving at the same speed?

The study team built a 3D mathematical model of a chiral active particle, meaning a bead that tends to twist around in a fixed sense as it moves. The particle had a constant forward speed in its own frame of reference and an angular velocity that would, in the absence of noise, make it trace a perfect helix.

The work’s novelty lay in how the team treated the rotational noise. Instead of adding white noise, the authors described the angular velocity with an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process. Here, the noise is ‘pulled back’ towards a preferred value with a certain relaxation time. This produced ‘coloured noise’, i.e. not just white noise but noise that was partly predictable, mimicking the slowly varying internal processes within the parasite’s body.

This model’s predictions of the bead’s average position and its displacement matched those of the parasites moving through the hydrogel.

Radius and pitch

Importantly, the authors found that in a 3D space and for a reasonable level of noise, a bead moving along a helical path could move a larger distance over more time than a bead travelling straight at the same speed. That is, given enough time, the helix could be “straighter than a straight line” in terms of how far the microorganism spread out from its origin. This behaviour differed from what many previous models had predicted.

The best-fit parameters of the new model also indicated helical paths with a pitch (the distance between two consecutive turns of the helix) of about 13 micrometres and a radius of about 3 micrometres. Both values fell well within previously reported ranges for these parasites. The shapes of the paths simulated using these parameters also resembled the ones the authors actually measured.

Taken together, the results suggest helical motion isn’t just a geometric quirk but a robust strategy for microorganisms like the malaria parasite to travel efficiently in noisy spaces. For a parasite whose internal ‘engine’ fluctuated on the same time scale as its turns, its rotating path could also average out those fluctuations and keep the overall direction of motion more stable.

The conclusion fit with earlier work on sperm cells and algae, where researchers had found helical swimming could help the cells move reliably in the presence of chemical gradients, even despite strong noise in curvature and torsion. The conclusion may also complement geometric models of malaria parasites that have emphasised the importance of their natural curvature and flexibility to help them stick to blood vessels of a comparable radius.

What goes around…

After a mosquito bite, only a small fraction of the sporozoites need to reach a capillary for the infection to succeed. And evolution seems to have figured the best way to ensure each parasite covers more ground before losing direction, without also requiring precise control, is to have helical motion with ‘coloured noise’.

“We suspect that this chirality developed during evolution to allow the pathogen to switch between the different tissue compartments in the host body quickly and always in the same way,” study coauthor and Heidelberg University professor of integrative parasitology Friedrich Frischknecht said in a release.

Beyond malaria, the model could apply to other microscopic swimmers such as certain algae and colonial choanoflagellates, whose helical paths and noisy propulsion scientists have already documented. The authors suggested the model could also inspire designs for artificial micro- and nanobots in medicine: by engineering a controlled rotational component and appropriate internal time scales, engineers could build small devices that navigate complex tissues more effectively than simply moving in a straight line.

A 2014 study by some members of the same team behind the new study treated the sporozoites as flexible rods interacting with obstacles. Subsequent models linked sporozoites’ shape with their ability to glide across certain surfaces. The new model seems to have added the missing ingredient: internal ‘coloured noise’. What next?

The authors concluded their paper saying they’d like to connect the timing of internal fluctuations to how organisms move, and then understand how those connections are shaped by where they live and how evolution has honed them.

Published – December 04, 2025 06:00 am IST

Leave a Reply