By identifying Plasmodium in human blood, Laveran shifted malaria from a disease explained by environmental theories to one understood through pathogen biology, enabling laboratory diagnosis, antimalarial drug development and vector control strategies that remain central to elimination efforts today

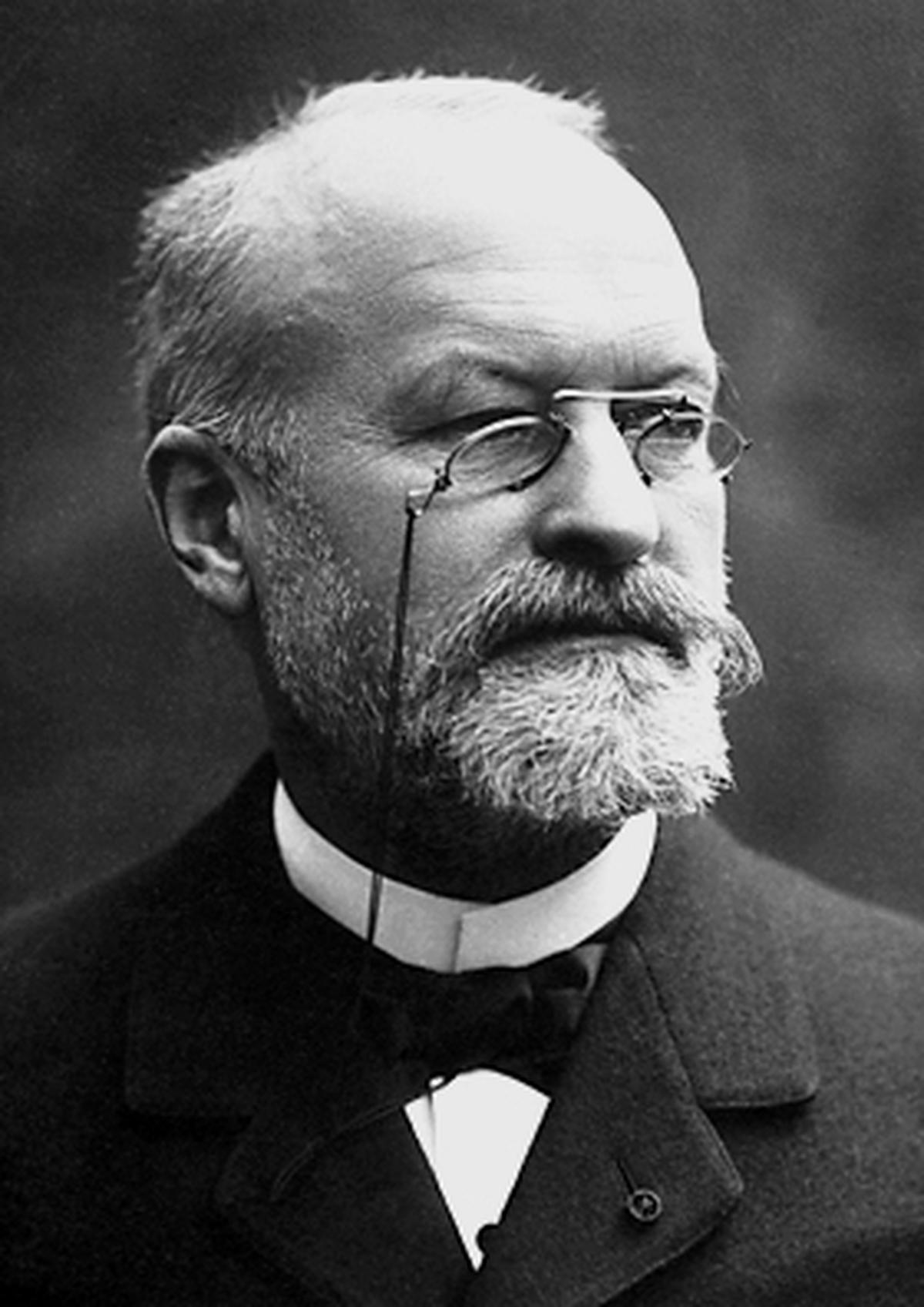

| Photo Credit: wikimedia commons

In 1907, French physician and parasitologist Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing disease.” His discovery in 1880 that malaria is caused by a protozoan parasite — later named Plasmodium represented a decisive break from prevailing theories that attributed the disease to “bad air” or environmental miasma. Laveran’s microscope observations in the blood of malaria patients not only revealed the biological cause of the disease but opened a new field of research in parasitic pathogens.

Early life and military medical training

Laveran was born on June 18, 1845, in Paris, into a family with a strong medical and military tradition. He studied at the École du Service de Santé Militaire de Strasbourg and later served as a military physician during the Franco-Prussian War. His extensive clinical exposure to febrile diseases, especially during postings in Constantine, Algeria, shaped his scientific curiosity. It was there, in a region with high malaria burden, that he made the breakthrough that defined his career.

Identifying the malaria parasite

At the time, malaria was widely believed to result from environmental influences. Through careful and repeated microscopic examination of fresh blood samples, Laveran observed pigment-containing, motile organisms — identifying them as protozoan parasites on November 6, 1880. This was the first demonstration that a protozoan could cause disease in humans.

Although initially met with hesitation in some scientific circles, his findings gained wide acceptance as other researchers replicated the observations, and later work by Sir Ronald Ross established the mosquito as the transmission vector.

Research expansions and global impact

After returning to France, Laveran continued his research at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he broadened his investigations to other protozoan diseases such as trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) and leishmaniasis. His work played a key role in shaping the emerging field of tropical medicine.

He published influential works, including Traité des fièvres palustres (Treatise on Malarial Fevers), which synthesised clinical and parasitological knowledge and guided early malaria control efforts. His research and advocacy helped lay the groundwork for modern parasitology laboratories, informed public health malaria control strategies, and supported the establishment of tropical medicine research institutes across Europe and beyond.

Laveran’s commitment to advancing parasitology extended beyond scientific discovery. Significantly, he donated the entire monetary award from his Nobel Prize to the Pasteur Institute, enabling the establishment of a dedicated laboratory for parasitic disease research — one of the first of its kind globally.

In the early years of malaria research, he approached emerging theories of mosquito transmission cautiously, before later recognising how his identification of the parasite and Ross’s demonstration of vector transmission complemented each other. During World War I, Laveran remained actively involved in laboratory research and served in an advisory capacity on parasitic infections affecting soldiers in colonial battle zones. Through these continued efforts, he played a formative role in shaping tropical medicine as an organised scientific discipline.

Legacy and influence today

Laveran’s discovery remains central to global health. Malaria continues to be a major infectious disease worldwide, and research on the Plasmodium parasite, antimalarial drug development and mosquito control strategies all trace their conceptual beginnings to his work. His research was pivotal in establishing protozoa as a major category of human pathogens, influencing the development of antimalarial therapies and vaccines, and informing vector control programmes, a cornerstone of global malaria eradication strategies.

Laveran died on May 18, 1922, in Paris. The legacy of his Nobel-winning discovery endures in every malaria diagnosis, treatment protocol and elimination effort — marking one of the most consequential milestones in the history of infectious disease research. The World Health Organization and global malaria programmes consistently recognise Laveran’s discovery of the malaria parasite as the foundation of modern malaria control. His work continues to underpin global health policy, including strategies led by WHO and the Roll Back Malaria Partnership.

Published – November 09, 2025 07:34 pm IST

Leave a Reply