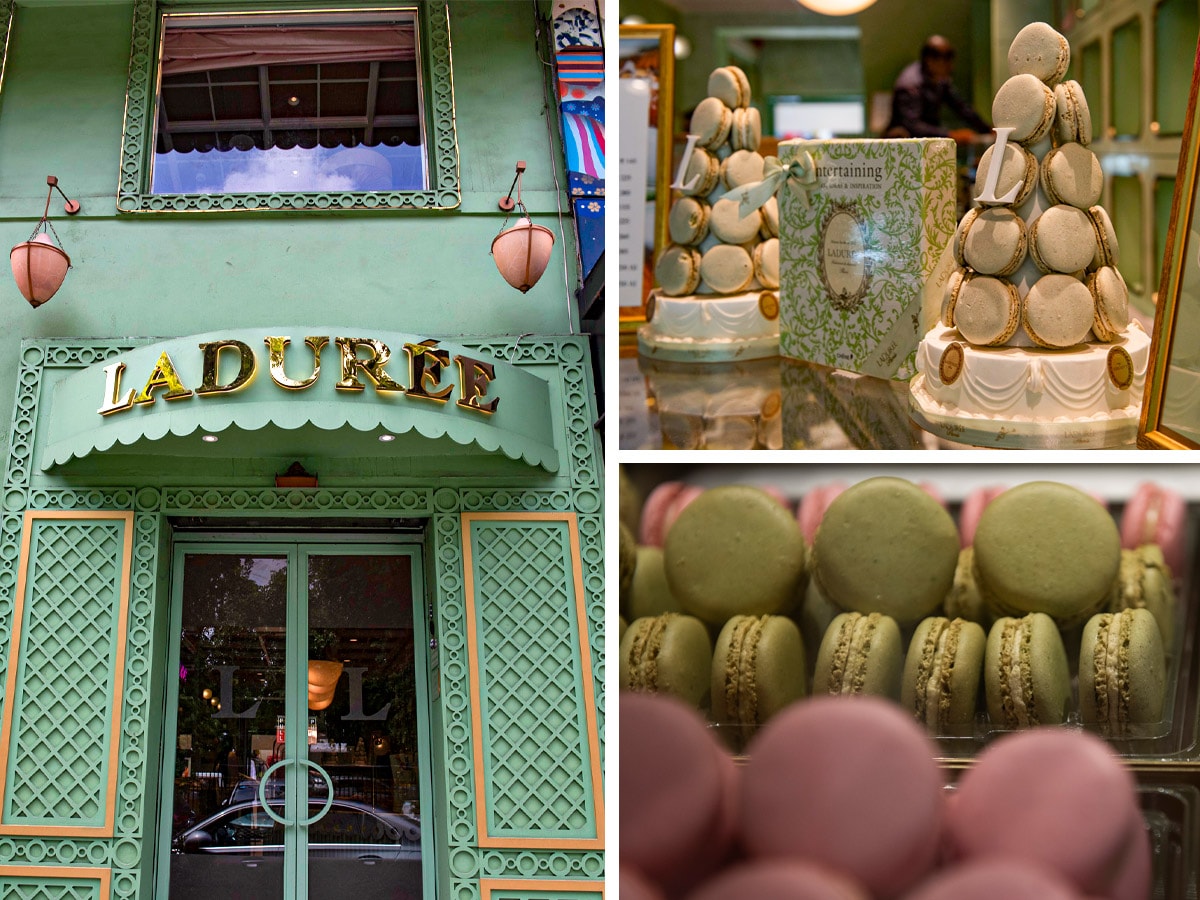

Chandni Nath Israni, who holds the India franchise for storied Parisian macaron-makers Laduree, at their Khan Market outlet

Chandni Nath Israni, who holds the India franchise for storied Parisian macaron-makers Laduree, at their Khan Market outlet

In January 2022, in the midst of the Omicron wave of Covid, Chandni Nath Israni, who heads the lifestyle vertical for the Delhi-based real estate company CK Israni Group, received an unexpected call from Kolkata. “A customer informed us he was flying down in his private jet to pick up Rs50 lakh worth of macarons,” says Nath Israni, who has brought iconic Parisian macaron brand Ladurée to India. “We delivered the consignment at the private hangar at the Delhi airport, and he flew back immediately after.”

Nearly three and a half years later, seated at a Ladurée salon at Mumbai’s Jio World Plaza, Nath Israni chuckles at the memory. But, back then, at a time business sentiment—especially in F&B—was reeling from two years of sporadic Covid-induced lockdowns, the order vindicated her faith: That a country known for its rich tradition of mithais still had an appetite for a super-premium French dessert.

Founded in 1862 in Paris’s Rue Royale, Ladurée has grown into one of the most celebrated names for luxury patisserie. It was here in the 1950s that Pierre Desfontaines, the grand-cousin of founder Louis-Ernest Ladurée, is said to have imagined the world’s first macaron—two delicate almond meringue shells filled with creamy ganache—that would go on to win over gourmands around the world.

But Ladurée’s India debut came at an ominous hour—Nath Israni signed the franchise deal with president David Holder in May 2020, two months after the first Covid lockdown was announced. With business at a standstill and shops shuttered, she was often confronted with a question: Who will splurge on a macaron that’s just a tad bigger than your average Rs10 coin and, back then, came for Rs225 apiece? “When we opened our first outlet in Delhi’s Khan Market in September 2021, as the Delta wave gradually waned, there was a kilometre-long queue outside the store. That was your answer to the question,” she says.

While the company had a slow start in India, tempered by the aftermath of Covid, it has since picked up momentum. Ladurée now sees a 20 percent year-on-year growth, and earns nearly 65 percent of its revenues from macarons. During this period, it has launched nine outlets in three years—“this after it took us one full year to open our second outlet after the Khan market one,” says Nath Israni.

Ladurée now sees a 20 percent year-on-year growth, and earns nearly 65 percent of its revenues from macarons

Ladurée now sees a 20 percent year-on-year growth, and earns nearly 65 percent of its revenues from macarons

The Growth Story

Ladurée’s growth trajectory mirrors a pattern in India’s evolving dessert landscape, where macarons, though a niche category, have been blossoming for a few years. At present, the numbers are modest—currently, macarons hold less than 1 percent share in the overall India bakery market—but they are projected to grow at a rate of 8 to 10 percent annually by 2030, says the Imarc Group, a market research company. “When we consider the product life cycle, most Western dessert categories in India are already in their growth or maturity phase. However, macarons are just beginning to enter the growth stage, indicating significant untapped potential,” says Rajesh Padhi, SBU head business research, Imarc. “At present, macarons account for less than 5 percent of the Western desserts market in India. We expect this share to rise to around 6 to 7 percent over the next six to seven years.”

Also read: The Bombay Canteen Celebrates Mithai With Its New Brand: Bombay Sweet Shop

A testament of the growth potential comes from the Mumbai outpost of Yauatcha, the tony London-headquartered restaurant now run by Aditya Birla New Age Hospitality, which sells 1.5 to 2 lakh macarons per month at Rs195 each, and where every third dessert ordered is a macaron. “For every sale of Rs100, about Rs6 come from desserts, of which macarons form a large part. With the aspirational middle class set to rise over the next decade, the craze for macarons will only grow,” says Sumeet Sharma, head operations, F&B and integration, Aditya Birla New Age Hospitality.

The most compelling narrative of the macaron’s ascent in India, though, isn’t told through numbers, but its elevation in public perception—from being dismissed as glorified ‘nankhatais’ to making their appearance at high-profile dos, be it the Tesla store opening in Mumbai or to mark Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri’s visit to the city during the WAVES Summit in May.

Pooja Dhingra, the founder of Le15, started from a shop-in-shop in Mumbai in 2010 and now runs four brick-and-mortar stores and a central kitchen

Pooja Dhingra, the founder of Le15, started from a shop-in-shop in Mumbai in 2010 and now runs four brick-and-mortar stores and a central kitchen

Some of these customised treats, stamped with the company insignias, were crafted by Pooja Dhingra, a Mumbai-based baker who studied hospitality in Switzerland and later patisserie in Paris, before returning to the city in 2010 to launch Le15, a tiny shop-in-shop operating out of a salon in Worli. Its unique selling point: Those pastel-hued desserts that she had first tasted in the French capital. The idea to turn macarons into a business proposition came when her father, known to be a fussy eater, bit into one while visiting her, and was hooked. “I realised macarons would suit Indian palates,” says Dhingra. “But, for the first few months, we didn’t really have a place to sell. I have literally gone to malls, set up tables and handed out free macarons for people to taste.” Cut to 2025, and 60 percent of sales for Le15, both online and from its four brick-and-mortar stores, come from macarons.

“When Ladurée came to India, I felt really good that someone renowned internationally for macarons has come in to open up the category,” says Dhingra, who has earned the sobriquet of ‘India’s macaron queen’. “It’s so much better to have multiple players coming in to expand product awareness. The fact that there are so many players now shows there is significant growth in the market.”

Luxury chocolates company Smoor clocks about Rs 5 crore of its annual Rs 200 crore revenue from macarons

Luxury chocolates company Smoor clocks about Rs 5 crore of its annual Rs 200 crore revenue from macarons

The Mumbai outpost of London fine-fining restaurant Yauatcha amps up its macarons game during the festive season, with collaborations with the likes of Tribe Amrapali (left) and designer Manish Malhotra.

Moving Beyond Borders

What’s fuelling India’s macaron moment? Two factors: The rise in international travellers as well as disposable income with the middle class. According to the India Holiday Report released by Thomas Cook and SOTC Travel in May, 3.02 crore Indians travelled to foreign destinations in 2024, an 8 percent rise over the numbers in 2023. “The first thing that most of our customers ask us after returning from international travels is whether we sell macarons,” says Kanchan Achpal, chief marketing officer of Smoor, a luxury chocolates and desserts company that attributes about Rs5 crore of its Rs200 crore annual revenues to macarons.

As awareness rises, so does appreciation for taste as well as craftsmanship. For instance, for all its appeal, a macaron isn’t an easy recipe to master in the hot and humid weather of India. The texture must walk a fine line: Crisp enough to crack gently, yet firm enough to avoid turning gooey. “But we’ve been noticing a change in the attitude of customers,” says Achpal. “Earlier, clients would come and tell us the macarons weren’t any good because they were breaking easily. Now, with growing awareness, they realise that’s exactly how it’s supposed to be.” What has also broadened the market in India, where vegetarianism remains a dominant choice, is the innovation around eggless alternatives with the likes of potato starch, aquafaba, what have you. “Once those variants were discovered, a whole new customer base opened up for us,” says Dhingra of Le15.

In its ‘Rise of Affluent India’ report, Goldman Sachs predicts that the ‘affluent’ in India will total 100 million by 2027, up from 60 million in 2023, making the country a playground for luxury brands. No surprises perhaps that Ladurée, which now prices each macaron for Rs275, sells 40,000 to 50,000 pieces per month; its salon-format stores at Delhi’s Khan Market or Mumbai’s Jio World Plaza, among the poshest retail addresses in the country, command an APC (average per cover, a key metric for F&B establishments) of Rs1,500, bordering on fine-dine pricing but within sniffing distance of profitability. “At the pace we’re scaling, we expect to reach profitability soon,” says Nath Israni.

She adds: “Ladurée’s India prices are the cheapest among its worldwide prices—even in their home country, they sell for €3, which converts to about Rs300. When I brought the brand to the country, my target wasn’t just the top 5 percent, but also the next 25 to 30 percent aspirational Indians who want a borderless experience.” Nath Israni breaks down international borders, quite literally, by importing macarons directly from Paris, a couple of lakhs at a time either by sea, or air-couriered with ice at -18°C before storing them at a temperature-controlled facility in Noida.

The Mumbai outpost of London fine-fining restaurant Yauatcha amps up its macarons game during the festive season, with collaborations with the likes of Tribe Amrapali (left) and designer Manish Malhotra

The Mumbai outpost of London fine-fining restaurant Yauatcha amps up its macarons game during the festive season, with collaborations with the likes of Tribe Amrapali (left) and designer Manish Malhotra

Festive Surge

As India slides into the festive season, beginning with Ganesh Chaturthi on August 27, patisseries expect a surge in macaron sales, especially for gifting. “India is a mithai-centric market, but a lot of gifting has moved from Indian sweets to chocolates and macarons,” says Sharma of Aditya Birla New Age Hospitality. “Macarons fly off the shelves of Yauatcha post-Ganpati as we sell 2.5 to 2.75 lakh pieces per month during the festive season, compared to 1.5 to 2 lakh a month at other times.” This is also the time the restaurant ties up with retailers for themed products to up the novelty quotient—like a navratna collaboration with Amrapali jewellers in 2024 or with the House of Masaba the year before.

Gifting was also what brought Dhingra and Le15 into the conversation at a time macarons were still nascent—one of her first big sales came with Forevermark, where she supplied macarons for their shows across the country. “We did Tarun Tahiliani’s show, our macarons as gifts were kept on the front row at a Being Human event, and in some time, I still don’t know how, they became part of the Koffee with Karan hamper,” she says.

Ladurée’s catering services are booked for at least three times a week as the wedding and festive seasons kick off in August. “We often get orders of 10,000 macarons for a single wedding,” says Nath Israni. What’s striking, she adds, is that demand isn’t limited to metros. “About 20 percent of our catering comes from non-metros, from cities like Raipur, Indore, Meerut, Gangtok etc.”

While Nath Israni wants to focus on Tier II and III cities as Ladurée’s next segment, most companies are adopting a wait-and-watch approach to scale up beyond metros. Sharma of Aditya Birla New Age Hospitality, who has family in Indore, believes the non-metros are still hooked on to their gulab jamuns and rasmalais, and it may be some time before a niche Western dessert like a macaron will be a go-to bite.

But a bigger problem staring at them is a suitable logistics chain for a highly perishable item like a macaron that has a shelf life of a mere 72 hours. Smoor hasn’t gone big on deliveries and their macaron business is confined to 75 stores across five cities, confirms Achpal, primarily constrained by logistics. Dhingra’s Le15 gets only 8.25 percent of their macaron sales from non-metros, currently served only through their website. But she holds out hope for next year. “We have finally worked out a system where we can freeze and ship macarons, which will enable us to move out of Mumbai and to other cities in a big way,” she says.

Dhingra recently went back to Bombay Scottish, her alma mater, to deliver a talk to 200 schoolkids. “When I asked how many had eaten a macaron, almost everyone raised their hands,” she says. “Ten years ago, I doubt even one would have.”

Leave a Reply