Every year between August and September, Natyarangam, the dance wing of Narada Gana Sabha, presents its annual thematic dance festival, which brings together eminent personalities including musicians, dancers, and scholars on the same platform.

The festival offers young talented dancers an opportunity to perform, and allows them to conceptualise and create a full-length presentation on the chosen topic. Each yearâs edition will have a different theme. This yearâs festival, titled âRithu Bharathamâ, is themed on the six seasons.

The theme provided an opportunity for the artistes to unleash their imagination and explore the myriad facets of each season. But the committeeâs guidelines to include a wide range of works â from Kalidasaâs to Sangam, and from Ragamala paintings to festivals â seemed difficult for the dancers to fully explore the essence of each season. A specific template, requiring the dancers to integrate their ideas, resulted in a similar pattern getting repeated on all days.

Rama Vaidyanathan segmented the season into five parts beginning with Saumya and ending with Apeksha.

| Photo Credit:

SRINATH M

The festival began with Rama Vaidyanathanâs âVasantha Rithuâ (Spring) performance. Rama had divided the season into five parts beginning with Saumya (season of Equanimity), Punaravarthana (Rejuvenation), Kama roopini (love), Bahu Varnani (multi-hued), and Apeksha (hope).

Rama Vaidyanathanâs Vasantha Rithu

Rama Vaidyanathanâs performance was titled Vasanth rithu.

| Photo Credit:

SRINATH M

Her description of night and day effectively conveyed the difference in the time cycle associated with the season. She built up the visual imagery with an interesting soundscape to enhance the ideas â the scattering of seeds, to a rhythmic melody of tanam; use of swara passages to depict different flowers of the season; and culminating on the lotus flower, on which goddess Saraswathi stands. A detailed exploration, for the song âSaraswathi namosthutheâ, composed by G.N. Balaubramaniam in raga Saraswathi, followed

The entry and exit for the section showing Manmatha gliding on his vahana Parrot was gracefully presented. The descriptions of the cool breeze, swaying palms, birds, bees, peacocks and deer were a little overstretched, negating the mood. Various aspects such as Raas, the use of colours during Holi festival, and the portrayal of Vasantha Ritu as a newlywed were well-explored.

Soundscape was conceived in an interesting manner by S. Vasudevan, who used instruments such as ghatam, kanjira, and sitar, judiciously for the sequences, along with suitable ragas.

Apoorva Jayaramanâs Grishma Rithu

Apoorva Jayaraman performing at Natyarangamâs Rithu Bharatham.

| Photo Credit:

SRINATH M

It was time to move on to the next season â Summer, as Apoorva Jayaraman performed âGrishma Rithuâ. Draped in a waistcoat on top of the costume, Manmatha made his appearance again. Apoorva chose verses from Kalidasaâs Ritu Samharam to depict Kamadeva. The drooping sugarcane bow, the wilting flowers of the arrow, and the tired parrot were depicted to convey the mood of lethargy and exhaustion that permeates the season.

Apoorva Jayaraman at Natyarangamâs Rithu Bharatham festival.

| Photo Credit:

SRINATH M

The issue of water scarcity was poignantly portrayed through a beautiful abhinaya sequence, which showcased a motherâs love as she quenches her childâs thirst with the little amount of water that she has, before embarking on a long journey to procure drinking water. While there are many descriptions to depict the seasonal impact of Grishma, the experience of the whole atmosphere and feel of the season were overshadowed by these narratives. Even the costume didnât reflect the colours.

Apoorva Jayaraman performed Grishma as part Natyarangamâs Rithu Bharatham festival.

| Photo Credit:

SRINATH M

Rhythmic jathis to denote flaming sun and fire, and a few swaras for depicting peacock were interesting, but a repeated use of identical musical phrases through out the performance, proved to be a deterrent.

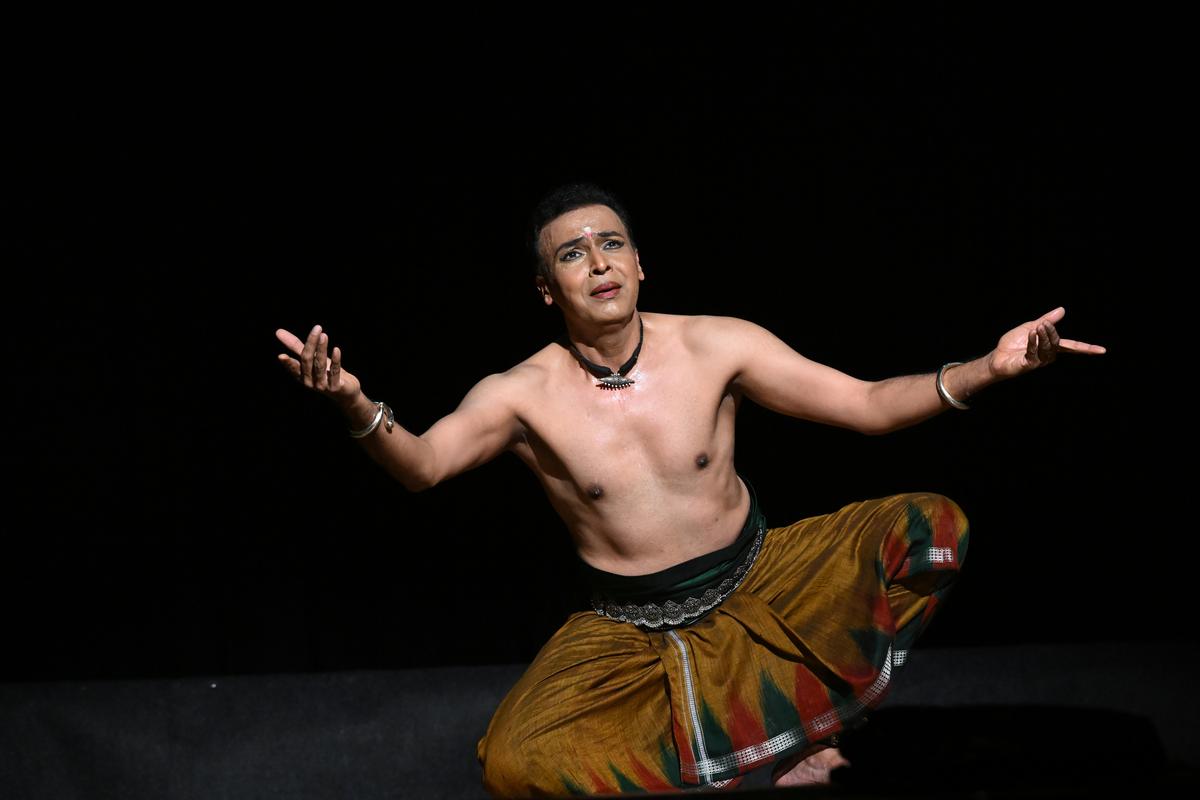

Vaibhav Arekarâs Varsha

Vaibhav Arekarâs (Varsha).

| Photo Credit:

SRINATH M

The focus of the series shifted to a mode of dance theatre, as âVarsha â Harvest of Lost Dreamsâ, a presentation by Vaibhav Arekar unfolded. With an interesting soundscape and a musical ensemble of talented artistes, clad in black attire providing stimulus, Vaibhav depicted âVarshaâ (rainy season) through an engrossing portrayal.

The premise of Vaibhavâs performance was based on a farmerâs connect with nature, and the emotions and situations that develop between them . It began with a visualisation of a man ploughing, tilling and planting the seeds, moving on to show his anticipation of rain to nourish the soil. However, when the rains didnât come, he experienced disappointment, coupled with the feelings of anger and distress during the fierce monsoon. The narrative concluded with the man bowing in total surrender.

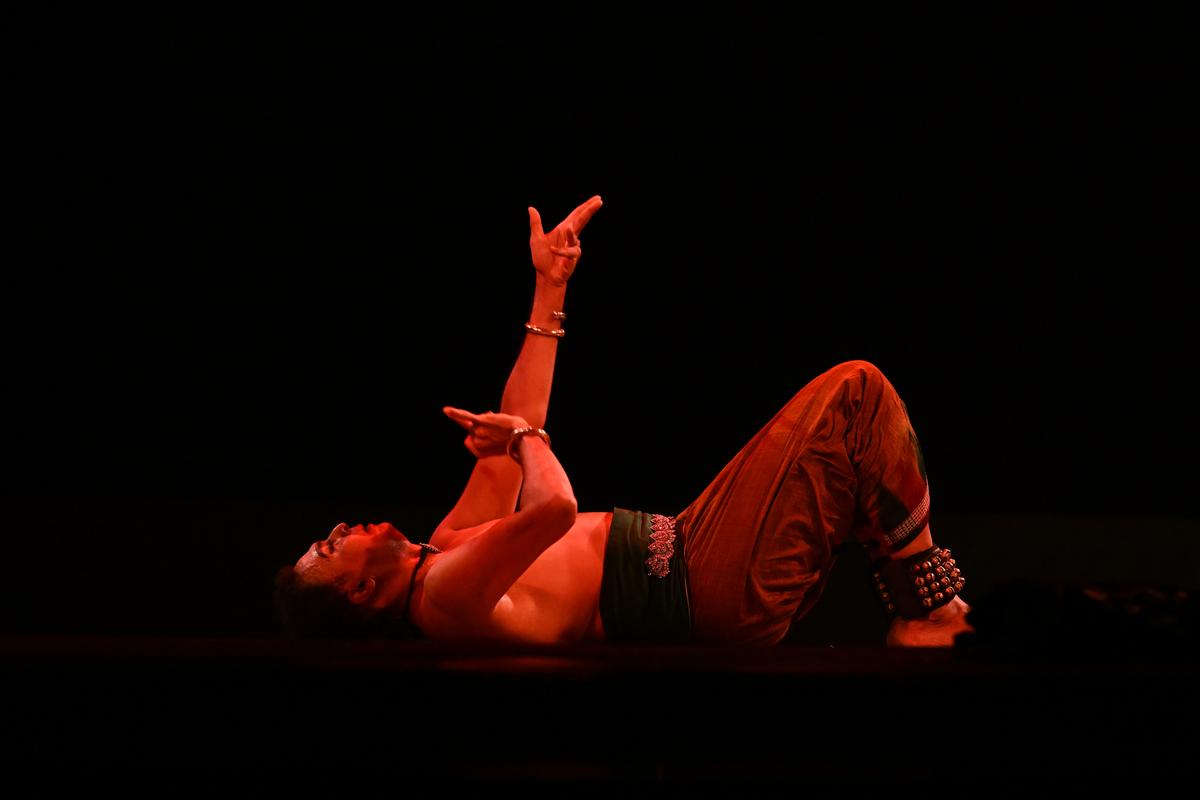

Vaibhav Arekar uses graceful and fluid hand movements to convey the idea of intimacy. He performed (Varsha) season at Natyarangamâs Rithu Bharatham festival.

| Photo Credit:

SRINATH M

The highlight of the presentation was the scene that featured a figure lying horizontally under a spotlight. The hands rose slowly with graceful and fluid movements, conveying a sense of intimacy in an arresting way. By drawing comparisons between the Sakhyam of clouds and Earth, and the emotional bond between a man and his beloved, Vaibhavâs theatrical approach made this sequence appealing.

Elements of dance such as Jathi korvais and adavus were used beautifully to convey the energy of the sun and the fierce intensity of the water. Dikshitarâs composition âAnandamrithakarshiniâ, a Sangam poetry, and works of Kalidasa and Bharatiyar were woven into the musical expression to suit the ideas.

For many, monsoon evokes a feeling of anticipation, joy and excitement. Â However, in this performance a brief exploration of that mood was depicted through a childhood memory, highlighting that angst, anguish, and fury are the predominant emotions experienced during the monsoon.

Visual images

Ragamala paintings are a treasure trove of visual images which highlight the moods of each season and even ragas and raginis associated with them. To use them as source material was indeed a good idea, but the way in which they were utilised here undermined their value.

Rama used a projected image of a frame, to suggest a character in a painting, but it could have been any painting, not necessarily Ragamala. Apoorva split the image into three fabric panels, distorting the art form. Vaibhav used it as a straightforward projection, and as a filler between dance sequences. Care could have been taken by the artistes and organisers to deal with another art form with greater sensitivity.